The following post originally appeared on Forbes | Mar 7, 2014

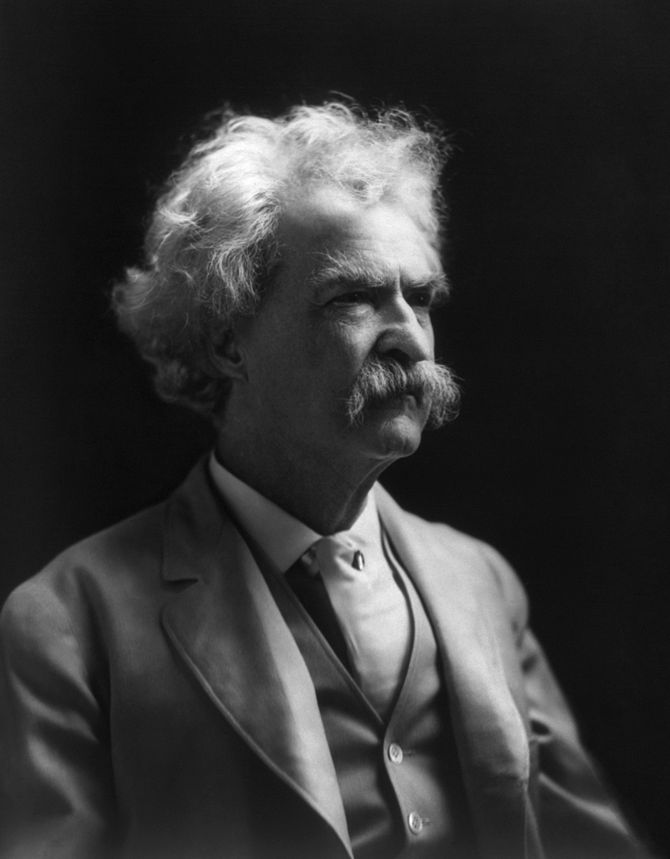

If Mark Twain were still gracing us with his presence, Patton Boggs might seek his counsel in dealing with a premature obituary. Their unity and stability have been something of a debate in the media recently, which seems bent on the firm’s demise. But alas, Mr. Twain has passed, so I’ll try to fill his shoes, starting with a tale from the past. (Twain fans will appreciate the rhyme).

It was February 22, 1980, and the US Hockey team was warming up for their medal-round with the Soviet Union national team at Olympic Center Arena in Lake Placid, New York. 20 young men cut the ice, almost brazenly, as they destroyed the Zamboni’s masterpiece. The screams of 8,500 fans couldn’t disturb the silence in their young, and as of that moment, seasoned minds. Brief, but powerful moments of lucidity gripped them: they felt their sticks in their hands; they saw their breath in the air; they smelled the sweat of their uniforms; they looked around, and through the melee of anticipation, and emotion, and athletic lust, they finally understood the meaning of their work. They were a finely-tuned, impossibly cohesive team that was chomping at the bit, ready to be sicced upon their victims like dogs of war.

Gathered for an impossible task, they were a group of former opponents, and in some cases, adversaries. The media never gave them a chance. Shoot, not even their closest friends or family gave them a chance. They were younger, less skilled, smaller, and in most ways that mattered, just plain outmatched by the Russians. But as the media continued their onslaught over the months and as the pressure from an entire nation gained critical mass, like any man does when faced with true adversity, they, for the very first time, experienced their true nature, and it was ferocious. It was something to behold.

The team had a plan: First, they would outwork the Soviets. This meant going back to basics and beating their bodies into hardened machines. Second, they would eat, breath, and sleep the pressure that was raining down upon them so as to rally a team that was so cohesive, so lean, and so incredibly strong that Wayne Gretzky himself couldn’t out-skate them. And through sheer force of will, by the time the final buzzer rang, the Americans beat the Soviets 4 to 3. The face of a sport, the face of a war, and the face of a nation had changed forever…

We’ll get to the metaphor in a moment. But first, what prompted this piece was an article I read in (Bloomberg) Businessweek: Will Legendary Law Firm Patton Boggs Be Swallowed or Evaporated? I had written about them (Patton Boggs) back in November. Sparked by the realities of a shifting legal climate, foresight got the better of their management team and they made some very bold moves – changes to their compensation model and culture, shoring up for the retirement of a named partner and industry icon (Tom Boggs), and open layoffs, among other things. Staying true to form, much of the media flogged them for their efforts, e.g., Businessweek’s article. Negative exposure like that can do things to a firm’s primary psychology, so I made a few phone calls to see how they were holding up.

When asked about the firm’s solidarity, Kevin O’Neill, deputy chairman of the firm’s Public Policy Department had this to say: “Overall it is pretty good. When people take jabs at you that are unwarranted, it tends to draw you closer together, much like a family. I think that there is tremendous respect for the job that Ed [Newberry] has done in tackling the tough issues.” He went on to say “…the partners have demanded that we get smarter and more effective so that we can be the best possible platform for all of our professionals going forward. We knew going in that there would be some pain, we got a little bit of public attention for that pain, but we are emerging on the other side of that leaner and stronger. The internal metrics are that we have made the changes necessary to have the historic profit levels, now it is up to the partners to turn that projection into a reality.”

Like a living character in a Lemony Snicket novel, the firm has played host to a series of unfortunate events. Similar to the rest of the legal consumption market, lobbying work–their bread and butter–is evolving. This, coupled with the financial downturn, the winding down of litigation work defending New York City and its contractors against claims relating to the Sept. 11 attacks on the World Trade Center, and the ill will of Chevron, has hastened the firm’s drive to re-engineer itself to better suit the needs of a changing legal market. Unfortunately, change is not a readily embraced strategy in the eyes of the legal community at large.

Late yesterday afternoon, I found myself discussing the history of challenged firms with Mark Sheridan, Patton Boggs litigator. Regarding the team’s loyalty, he said “It’s a gut check moment here. You’ve seen this movie before, and you know how it ends most of the time. And I think that what the partners at Patton Boggs are saying is, yes, we’re in the middle of act two of that movie, but rather than having act three where everyone leaves, we’re going to stick it out, and that is what was internally displayed on Friday.”

Specifically, he was speaking of the partnership’s response to a firm-wide question posed by managing partnerEd Newberry regarding their future: “Who’s with us?”

If you missed it, Patton Boggs recently announced that they are in merger talks with Squire Sanders, a Law360 top 10 global law firm. Naturally, firm solidarity and buy-in are requisites on both sides if a merger is to proceed. The response to his query was unambiguous: 90% of the partnership responded positively. And while this is a powerful number where merger acceptances are concerned, in a media-induced position of tenuity, this still leaves some room for translation.

Patton Boggs has proactively cut weight over the past year. Fiscal stability was their goal, so presumably the group that is left comprises a stable of net positive producers. There is stratification to every team, however, and no one can guarantee full unity. With law firm infrastructure being as fragile as it is, the remaining 10% could be fatal, depending on the sway of the partners that constitute it. A partner who chose to remain anonymous described the bulk of the 10% like this:

Some people make [non-equity] partner, and they get paid [$X] a year. They then have a year where they put up $1.2M in business, and in the grand scheme of things, that pays about [$X+50K]. And then they are thinking to themselves, ‘I just lost $50K, I want to be an equity partner’ [because equity partner would have been paid another [$X+100K]. And they push, and they push, and they make equity partner, and what happens next year? They generate $800K in business, and they make [$X-50K]. And they say ‘what the hell happened?’ They left the comfort and protection of the non-equity position, and they didn’t produce the required work. I hear it from mostly younger partners who have just moved over from non-equity. [Some of the] guys who recently moved over were having trouble generating the business.

This isn’t unique to Patton Boggs. It is a positional challenge, and a market problem. Fortunately, the firm is fairly lean at this point, and doesn’t expect to see much more attrition. In a state of flux, however, which Patton Boggs is currently experiencing, there is certainly some lateral loss still waiting in the wings. Of consequence are the two sides to the departure coin: Heads, partners within the firm can get frightened by the potential for an avalanche and run to get out in time. The propensity for this is often a function of cultural strength and congruity of the firm’s compensation structure with the fiscal and working appetites of the partnership. Tails, clients see the media flaunting the departures, potentially get nervous that the firm won’t be around in 6 months and demand that their law firm counterpart find more stable shores. The propensity for this is a function of partner/client relationship strength and partner credibility in the eyes of the client.

With that in mind, here is the challenge for a firm in Patton Boggs’s position: some partners are going to leave, and unfortunately, those partners are not characterized in the media. This makes it challenging for onlookers to extract meaning from the departures. Who left who? What was their standing within the firm? Did they have a large book of business? These questions are rarely answered, yet are imperative to understanding the true signal to the market.

BigLaw is still very much a gentleman’s (and women’s) club. Poorly performing partners, when asked to leave, are not discussed publicly on their way out the door. Strong partners that proactively decide to leave often sign non-disparagement agreements; for those that don’t, in all but a handful of incidences, they won’t bad mouth their former home, anyway. Further, titles in BigLaw can be quite misleading, as “management” isn’t always synonymous with a large book of business or heavy internal sway. Tenure isn’t an accurate marker, either; just because a partner is very junior or senior isn’t a bulletproof measure of their standing within the firm. Lastly, let’s face it, when partners leave, sharks smell blood-that’s what sharks do. Only romantics and poets smell roses… So, unless a departing partner is an industry celebrity-which can speak volumes-the average legal client, and certainly the average onlooker, are left reading tea leaves. This is where Patton Boggs’s challenge lies: signals sent to the market in the event of any further departures.

You see, if there is a dangerous outlier for them at this point, it may be media-spooked clients. The slippery middle class-generally partners with $1-2M books that have not been able to galvanize their client relationships-may have difficulty pacifying client concerns. In a cohesive firm, this is usually just a matter of getting help from the firm’s better-known elders. And in a homogeneous, cohesive, team-oriented culture, this should happen without asking. Where Patton Boggs is concerned, the culture seems quite strong. In my conversations, I didn’t speak with a partner that refuted that. While there certainly are some naysayers left wandering their halls-every firm has them-I didn’t manage to reach any. In fact, here is how Robert (Bob) Luskin– Patton Boggs partner, and one of Washington’s most revered, and in some cases, feared, litigators–described the relationship between the firm’s senior and junior partners:

They’re [the middle class] obviously getting calls everyday [from recruiters] saying I can place you here and I can place you there. And they are coming to me and saying we are getting these calls, what do we do? My response is ‘we are a team.’ If something disastrous happens, I will take care of you, you do not need to take care of yourself. Interestingly, if you look at the departures from Patton Boggs, they are not team departures. A lot of these firms, as they start to unravel, they unravel in chunks. We’re not. We’re losing people one at a time, which tells me that there is a team culture in place.

Patton Boggs, with their former “eat what you kill” compensation model, was traditionally a confederated group. The partnership has rallied, however, and their vote to pass a new, more team-oriented compensation model is their way of putting their money where their mouth is. I see a partnership that is working together, rather than individually, to continue building a more seaworthy capsule.

When performing research for my upcoming book on failed law firms, I found several that were posed with the same challenges we’ve addressed here. Patton Boggs differs from those firms, however, in the proactive, stabilizing initiatives that they levied over the past year. The majority of their departures were strategic; the signals sent to the market should be different, despite the media painting them otherwise. With that being said, the cohesion of the team is being tested as we speak, and time will tell if their efforts ultimately pay off.

Let us now return to our metaphor: Pressure is a funny thing-it can make diamonds or dirt. In the case of the 1980 US hockey team, it made diamonds. And in a certain sense, Patton Boggs is the legal world’s version of that team. Whether they or the legal market in general realize it, there is much more riding on their success than just a brand. Patton Boggs is BigLaw on the brink. If you can’t see that, you’re not paying close enough attention. The cross they bear represents an extreme version of the pressures, challenges, and realities that many if not most of their competitors face. To the properly informed and trained eye, Patton Boggs has done the right things. They put in the work; they sacrificed and have to date, endured. In light of that fact, the success of this firm will create hope for many firms that sit just a stone’s throw away from them. At the same time, should they fail, even the hardiest of law firm management will quiver, because if Patton Boggs’s strategy doesn’t work, what will?